|

I

have a passion for the difficult and unusual: a little like me,

really! So it will come as no surprise that I model classic

airliners in 1/72nd scale. When I started out there were

very few on offer; airliner modelers worked in 1/144th.

One of my earliest ‘successes’ was converting an Airfix

Sunderland into a Sandringham. I filled in the round windows,

turrets and bomb racks with Milliput, and cut new square windows. I

shaped and sanded the model, sprayed it silver and was hooked.

Heller’s Connies and DC-6’s followed, as did numerous Daks but

what I really wanted was Imperial Airways and BOAC in their heyday.

This meant vac-forms! I

didn’t think I was good enough for the challenge but after much

procrastination bought a Carvair to join my Bristol Superfreighter.

I was careful to follow instructions and ended up very pleased with

the result.

Vac-forms

and resin products have proliferated over the years and I now have a

collection of some wonderful models. Then I discovered Combat Models

from the USA and their big ’boats! I have still to make the

Dornier Do-X (Hilton Jones’ model of this is fantastic!) but I did

make the Boeing 314 Clipper (written up for SAM in 2002). Then at a

model show some years ago I came across an old Contrail model of the

6-engined Latecoere 631. I bought it, cut out the main components

and then shelved it. It looked huge and somewhat daunting. My modeling

progressed and I made the excellent Aerovac (a French

company) vac-form of the Latecoere 521, the 631’s predecessor.

Finally feeling confident and interested enough, I dug it out to try

again.

Then

I made a fateful decision: I wanted this to be the best and most

detailed model I had ever made. On the Late 521 I cut out and

lowered the flaps, ailerons and elevators, and off-set the rudder.

It made a huge difference. I would do the same on this model and

‘super-detail’ it! I have also decided to write up and

photograph my progress rather than report on the finished product.

We shall see how I get on.

History

In

1936 the French Air Ministry issued a specification for a large

transport flying-boat capable of carrying 40 passengers over 6,000 kilometers

against a 60kmh headwind. Three firms designed planes to

meet this specification but only the Latecoere 631 eventually made it

into production. Construction started in March 1939 in Toulouse but

was interrupted by the outbreak of war.

There

followed the most extraordinary story..............

After

the armistice, construction resumed under the Vichy government. As

Biscarosse was in the occupied zone the decision was made to assemble

and test the prototype (and the other two prototypes: the LeO H-49 and

the Potez-Cams 161) at the Etang de Berre. All three planes were moved

by road convoy from Toulouse, where they were built, to Marseilles

where they were assembled and readied for testing. The Late 631 was

given the registration F-BAHG and was painted grey with orange nose

and wings.

The

testing, despite onerous conditions imposed by the Germans, was

successful but in January 1941 the Late 631 was confiscated by the

Luftwaffe and flown to Lake Constance where it was unfortunately

destroyed by Allied bombing. While all this was going on in Marseille,

the second prototype, 02, was under construction in Toulouse. By March

1943 it was almost complete. But the Germans wanted the factory for

the Junkers Aircraft Company and the Late 631-02 for themselves.

Latecoere

had other ideas. They persuaded the local authorities that the plane

should be ‘sheltered from Allied bombing.’ It was then dismantled

and spirited away. Pieces were hidden all over the Haute Garonne

region. Typical places were the local sheep pens and a pig farm! The

fuselage was buried in a cutting, covered with branches and was

guarded by the local population. It became the Maquis’ secret plane.

They then blew up the factory!

Some

months later, in August 1944, Toulouse was liberated. The huge plane

was unearthed from its hiding places, the gutted factory was rebuilt,

the plane reassembled and, by December, it was on the road to

Biscarosse. The convoy was over 400metres long. It is quite the most

astonishing story of deception, guile, bravery and determination

rewarded, eventually, by a very successful first flight on 6th

March 1945.

But

the fairytale was over. The world, and France, did not need big

flying-boats as concrete runways littered the globe. Within 10 years

not one of the 9 Late 631’s built would survive. However it was, for

a few years anyway, the only French plane modern enough and large

enough, to cross the Atlantic.

The

Late 631 was a high wing cantilever monoplane with a two step hull,

twin fins and rudders and retractable stabilising floats. It was all

metal with a wingspan of 57m (188ft) and full span ailerons and flaps.

The 142ft fuselage accommodated 46 passengers in several separate

cabins. There was a restaurant, bar, numerous direct exit (!)

lavatories and aft, a kitchen. All the passenger berths could be made

up as beds. The huge upper deck housed the flight deck, a navigation

room, engineers section and the radio room. In the bow was the mooring

compartment.

Building the Model

I

cheat. I use power tools whenever I can; it makes life so much easier.

I certainly could not do without my rotary tool because not only can I

drill out the windows, well holes in each corner and then much

patience with a knife, but with a sanding tool it makes short work of

shaping the huge parts.

Figure 1: It's Big!!

Figure 2: showing the window cut outs

Construction

- The

Fuselage

The

first job was cutting out and shaping the windows. It is not

difficult, just time-consuming. I drilled as many holes as I could in

each window aperture and then shaped them with a knife. Like the

Boeing Clipper the Late 631 has small upper berth windows. On the

Clipper I simulated them with black decal; on this one I drilled them

out! It’s very fiddly! I then cut out the doors as I intend it to be

as detailed as possible. This of course meant building an interior. I

started off putting the kit provided bulkheads and floors in and then

began detailing.

I

started with the flight deck. Two metal seats are provided as is the

‘dash-board.’ I scratchbuilt, from plastic card and sprue, the

instrument panels, navigator’s and engineers panels, the distinctive

autopilot column, the throttles and various other small details. Then,

from the spares box, came the steps and extra bulkhead, complete with

door, for the bow mooring compartment.

Figure 3: cockpit detail

Then

I tackled the aft main entry compartment. Plans show toilets opposite

the entry door so out came the plastic card again. Amidships there is

another door, presumably for crew use. This opens into a two berth

cabin so I needed to build the cabin. I then looked through the door

and realised I had to build the four berth cabin opposite and the

adjacent toilet compartment. So I did. Seats came from the scrap box,

wall from plastic card. At this point I realised that if I was not

careful I would have to build the whole interior. But if I curtained

the windows and sprayed the unseeable parts black I might get away

with it. So I did! That’s 96 curtains! When I built the Clipper I

glazed each window with clear plastic cut from a box top before

masking each one prior to spraying. I don’t want to go down that

route again as I don’t think it was very successful; instead I will

revert to my usual style of filling the window apertures with

clear-drying PVA. I am hoping that having the curtains, colourfully

painted, will help.

Repeated

checking of the fit of the two fuselage halves was continuous. Next

came the black spray can. I sprayed the whole of the interior black

before masking and spraying the centre cabin cream and the bow mooring

compartment and aft cabin silver. Then came the detailing. Although I

have excellent references and have used them to plan the general

layout the museum at Biscarosse has a mock-up of a 631 cabin, how they

used to travel in those days! I have also made considerable use of modeler's

licence on the grounds that it is better to see something

through the canopy and doorways than very little highly accurate

detail hidden by bulkheads and that only I know is there. The mooring

compartment gained ropes and fire extinguishers, painted red, and the

flight deck received dials, notices, knobs, seat belts and maps. I

then joined the fuselage halves by taping them together and running

thin superglue along the joint. A considerable amount of filler and

sanding later I have what is beginning to look like an airliner.

The

Tail

Figure 4: the tail parts

Now

this is where thing start to get complicated, but as in so much else

patience, ingenuity and common sense will ensure that it works out in

the end. I hope! The main complication is that the parts are not the

same size or shape and the panel lines are in different places. So

having scraped and sanded the edges to get the thinnest possible

trailing edge, I joined the various halves together. I put plastic

tabs at the end of the tail planes to aid the joining of the fins,

before scoring around the outlines of the elevators and rudders. They

were obviously not designed to be cut out as none of the lines meet

up! Perhaps I should have cut them out before joining the halves

together but that would have created more problems. As it is I am

going to fill the spaces with small strips of plastic card and then

shape them all to fit. It will be time consuming but should not be

difficult. I am dreading assembling the main wing! I’ve done it! At

least I have filled in the gaps with plastic card and filler; I have

yet to start the sanding/shaping.

Intermission!

I

am now thinking about the main wing flaps. I think they are the

extending ‘Fowler’ type flap and what I need is a kit like that

for the B-377/ B-50. As I don’t think it is currently available and

probably wouldn’t fit anyway I will have to think again. At the

moment it looks like cutting them out, making up the flap with card,

lining the wing with ‘ribs’ and then hoping it all goes together.

I

never thought it would happen to me (well you don’t do you?) but

while working on the fuselage cut out for the tail wings I managed to

glue my fingers to the plane with super-glue! While Doris Day and Rod

Taylor were gleefully cavorting around the telly as make-believe spies

I was busy trying to pry my fingers free using Locktite glue remover

and SAM’s scale rule; (I knew it would come in handy one day!) all

of it much to the amusement of my wife. It had happened as I was

running some ‘super thin’ glue inside the main fuselage join which

had come apart after I had cut away the area where the tail plane

sits. I had just completed the sanding and finishing of the tail plane

and fins and now need to fit them to the fuselage. They actually look

good; all that hard work has paid off.

It

is now some weeks later, my fingers have recovered and although I have

been doing some modeling I haven’t actually been doing any writing

up as I have been busy setting and marking exam papers. Having spent a

great deal of time on the internet trying to find new photos or

drawings of the large Late, with little success, I have realised that

lowering the main flaps is more likely to be educated guess-work

rather than known fact but I will go ahead anyway. The one photograph

I do have suggests that they extend a little and then droop, relying

on shape to increase lift, so this is what I will attempt. I have also

discovered that the outer nacelles that house the retracted floats

also form part of the flap, presumably the flaps could only extend

when the floats were lowered. This does complicate matters a little

but I am sure I shall manage.

Back

at the tail!

The

tail now looks very good. Having attached it to the fuselage and

lining it up by rack of eye I spent several hours with filler,

sandpaper and glue refining the final shape. The separated fins and

elevators fit in their respective slots but it did take a lot of work

getting them to an acceptable shape.

The

Engines

Six

engines! The two outer nacelles also house the floats, and, as I have

just worked out, also have to hinge with the flaps. Anyway I cut out

and sanded all the engine halves, initially using my mini-drill with

sanding disc followed by a sanding block. I had already decided not to

use the awful kit engines but rather white-metal replacements from

Aeroclub. So I cut out six discs of plastic card and slotted them in

level with the cooling fins before joining the nacelles together. I

did not join the rear of the outer nacelles together in the belief

that it would aid their later fitting. When all was dry I fitted a

rotary sander to the mini-drill and attacked the engine fronts.

Figure 5: The engine

fronts

They

needed a lot or rounding and I felt the cowlings were too narrow. Also

I could not get the engines in if I did not widen them! I then cut out

the ‘float’ part of the outer nacelles and the doors. Then came

the inevitable final sanding, shaping and test fitting. With the wing

not yet built this latter part was just guesswork!

The

Main Wing

I

sanded the wings in the traditional way and then put them together.

Each wing half was a different shape so the putting together was

purely hopeful. I did try to line up the aileron lines though. The

trailing edges needed a lot of filler and then I shaped the wings.

They are very flimsy and there is no obvious means of attaching them

to the fuselage. Fortunately a rocket landed in garden a few months

ago (a firework in November!) and the stick makes an ideal spar.

Holding the wing against the fuselage I drew in their positions and

then cut holes for the spar. To get the correct dihedral I sawed ¾ of

the way through the stick before gluing and stapling it to the correct

angle. (I have no idea what the angle is, it just looks right!) Quick

setting epoxy secured it in place and will also hold the wings in

place. The wingspan of the real thing is only 7 ½ feet less than that

of a Boeing 747, and it was designed in 1938!

Now

the challenge...........

Figure 6: Overhead view of the

ailerons

In

the end it has not proved as scary as I had expected. I scored round

the flaps and ailerons with a scoring tool from Bare Metal in the USA

before using a knife to cut them out. The wings are now even weaker,

but fitting plastic card, suitably shaped, into the gaps has helped to

strengthen them. Card has also backed the flaps and ailerons. It’s

actually looking quite good now, unlike our Rugby and football teams

who both received a hiding this weekend!

I

have now finished the wing, unfortunately without putting fingertips

to keyboard until now! This means that I have fitted the engines and

tested out the flap and aileron placement. I soon worked out, luckily

before gluing, that the four inner nacelles are not the same (they

look identical!) and must be fitted in the correct places. This done I

numbered them so when I did stick them they were right. All needed a

considerable amount of filler to blend them in. It was a case of fill,

sand, check, fill, sand and after a final check, coat with poly glue.

This has the effect of filling any minor blemishes and gives a smooth

surface ready for the final rub down. Once that was done it was a

matter of fitting the various intakes. I really did not feel like

fiddling with tiny vac-form parts so I raided the ‘spares box’ and

a Sainsbury’s fruit drink carton. The former offered up some DC-3

intakes which fitted neatly to the tops of the engines and the latter

a plastic drinking straw which, when cut in half, made perfect lower

intakes.

|

|

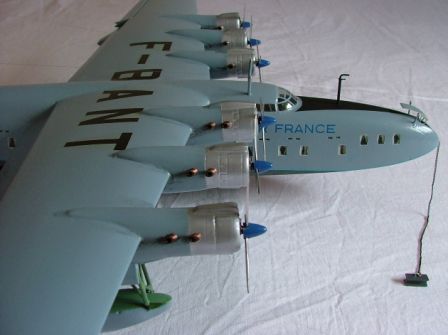

Figure 7: the wings, flaps

and engines

While

all this was going on I also managed to sort the flaps and the floats.

The flaps were rounded with filler and then, to make them look more

‘realistic’, and this is just guesswork as my references have few

decent pictures of the flaps, I fitted some fine screws to make

extending mechanisms. I now think they are hinged father than

extending so I will model them thus. The floats are pretty basic so I

enhanced them by cutting notches in the fronts to make the retraction

mechanism look more realistic. Again it was not difficult, just

finicky as it meant cutting and shaping the notches then lining them

with plastic card. I placed the card quite ‘crudely’ then, when it

was dry and strong, cut it to shape. The floats needed a bit of extra

shaping, but even so they are not the same shape or size as each

other. I hope no one notices!

I

have now got to the stage of final

assembly! This will require plenty of 5-minute epoxy and layers of

filler. Well, here goes!

Final

Assembly

The

first job was to attach the wings. I had wooden spars in place so I

just covered the ends with quick drying epoxy and held on! True to

form the wings were not quite identical but with considerable help

from ‘Mr Milliput’ and my mini drill sander they do at least look

vaguely level.

Figure 8: The wing span is huge!

Incidentally,

while rereading one of my references, ‘Histoire et Maquettisme’ I

discovered that this French language periodical had in fact commissioned

this model from Contrail to accompany the article in the magazine. It

was spread over two issues but I only have the first, and it

came with the model! I wonder if Neil Gaunt [AIM own the Contrail

moulds] will re-release it?

The

model began to take shape and I couldn’t help thinking of the brave

men who hid, and then rebuilt, the original. Filler around the wing

roots completed the blending in of the wings and fuselage; varying

grades of wet’n’dry completed the job. Again it is not difficult;

it just requires patience, and fortunately she is in constant

attendance. Going the whole hog I then fabricated ‘flap track’

from lengths of tubing just to add that little bit of extra detail. It

is probably wrong but it looks better than plain plastic. I did the

same in the float nacelles: adding ‘tracking’ for the supports and

retraction mechanism and nacelle door levers adds that little bit

extra. I am not a detail fanatic but on a model of this size bare

expanses of plastic are not realistic! Fitting the flaps was straight

forward (after trimming one to size, as I said each wing is slightly

different) and they certainly add something to the model.

Figure 9: the flaps

Fitting

the rudders (offset slightly), elevators (drooping slightly) and the

ailerons (one up, one down to match the rudder turn) was next. I used

superglue and was careful not to overdo the angles. Photos show that

under the wings there are what appear to be large aileron actuating

‘thingies’ but I can’t see how they are supposed to work so I

have modeled them as lever actuator by adding fine fuse wire to make

the rods. I based this on the mechanism of the big ’planes

predecessor, the Late 521. Again it may not be right but it

looks good!

The

Late 521 is modeled by Aerovac of France in 1/72 and is an excellent

and straight forward vacform, but on that one too I offset all the

flying surfaces. It has made into a most impressive model.

I

next fitted the Aeroclub engines. For this I used quick setting epoxy

as I needed to make sure that the engines all appeared level and

straight otherwise the props would all be at different angles. Plenty

of epoxy spread on the back of each engine and then pushing the engine

gently into the nacelle and holding it for a little while with a prop

in place made sure they all look even. It was as straight forward as

it sounds!

I

am not a happy man. I should not have put the floats on before

painting, I should have air-brushed not sprayed, in short I am feeling

depressed because my magnificent model is going to need a lot more

work for it to be truly magnificent.

The

Floats

Figure 10: the float assembly

As

readers may have gathered from the preceding paragraph I fitted the

floats before painting. This means that I have to hand paint the

struts in situ, not an easy task. The floats themselves went on quite

well; I made up the front supports. I glued them in place and then

attached the rear strut at the same time as the float.

Then

came the aerials. Always the weakest part of any model I decided that

as they were so prominent on this model I would make them strong. They

are made of paper clips, with the larger aerial covered in plastic

tube. They will have nylon thread strung between them.

Painting

Even

by this stage I was still not quite sure which ’boat to do. All too

many aeroplanes of this era are either all silver [aluminium] or

camouflaged and I wanted something different. Rereading, yet again, my

references, but this time for colour scheme, I came across a picture

of F-BANT that was not aluminium. The text said it was painted,

probably blue. Further reading suggested that F-BANT was the second

631 built, in 1942, and was the one dismantled and hidden by the

Maquis. It was reassembled in ’44 and ’45 and made its first

trans-Atlantic flight in October 1945. The kit provided decals for

F-BANT

but gave its colour scheme as natural metal.

Figure 11: the only place to

spray was out in the garden!

I

opted for the blue version and car spray paint! After masking the

cockpit canopy and the window apertures I sprayed the ’plane with

Halford’s Plastic Filler Primer. It took two cans! After doctoring

the revealed imperfections I rubbed it down with a scouring pad and

sprayed it with 2 cans of Ford Ceramic Blue. I rubbed that down with a

scouring pad, removed the masking and gave it two coats of Johnson’s

floor polish. The decals were old and yellowed but with the help of Mr

Johnson’s marvel the main lettering went on. I threw the rest out

and used spares box replacements. Then the detail painting started.

Engines, rudders, window surrounds, curtains, canopy framing, float

recesses, antiglare panel, doors, and planning bottom all needed to be

done. Masking tape to give crisp lines is essential. A final coat of

Klear sealed it all.

The

picture below shows the front detail.

Finishing

Touches

Aerials

were made of invisible thread, i.e. smooth ‘smoke’ coloured nylon

which gives ‘scale thickness’ but is almost invisible. Door hinges

were fashioned from paper clips, door handles from fuse wire and the

doors hung. Aeroclub metal propellers were polished, blue spinners

were added [reshaped DC-6 units] and the props attached to the engine

fronts.

Finally

I made a ‘beaching cradle’, my own invention but based on one

lurking in the background of one of my photos, and, raiding my

wife’s jewellery box, a mooring chain made from weathered Sterling

Sliver!

Figure

12:The Bow mooring compartment

Figure

13: 6-engined

monster!

The

real F-BANT, named Lionel du Marmier, went through all sorts of trials

and tribulations, including shedding a propeller in mid Atlantic which

wrecked a few passengers, their cabin and an engine, forcing the pilot

to complete the crossing on only 4 engines: 3 on one side and 1 on the

other! Like me, it always seemed to be in trouble when young but was

never allowed to grow old gracefully, finally being scrapped in 1956,

some years before I was born. The model took me the better part of

eight months to build and there were times when I felt like scrapping

it too, but I am pleased with the final result. My next ’boat? The

1/72 Do X from Combat Models!

Door

and flap detail

Figure

14:F-BANT

as she may have been in October 1945.

Bibliography

Aeroplane

Monthly, January 1993.

Histoire

et Maquettisme, September 1989.

[Le

Musee d’Hydravaition, Biscarosse, France.]

The

World Wide Web, but it does not have any more than is available from

the sources above.

|